Who wouldn’t love to find an old diary?

I found one in the summer of 2020. The story in it wasn’t a crime, but the tale from 1945 has lived in my head and played itself on a loop ever since June of five years ago.

I’m Brenda from Vintage Texas Crimes, and I’ve got a new story to tell you about a young woman named Marie Baker, who lived in Fort Worth during World War II.

Now, this isn’t a crime tale… I don’t want you to be disappointed. But if you like stories about Texans, this one will be a good one.

And just putting it out there… some behaviors should be a crime. See if you agree with me!

Marie Baker’s Diary from 1945

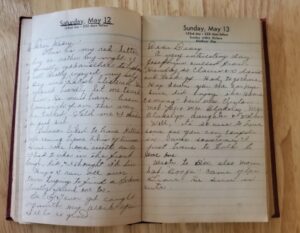

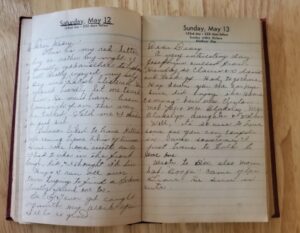

In June 2020, I was cleaning out my late mother’s home and getting it ready to sell when I came across a diary in the sea of things she left behind. It had been written by a young woman named Marie Baker. I had never heard of her, but five years later, I still can’t get her out of my mind.

There was no reason for the diary to be in my mother’s house. Maybe she found it somewhere, or picked it up at a thrift store. Marie Baker wasn’t related to our family, so the diary’s presence was a mystery.

My mother had amassed enough stuff to fill a museum—the kind that’s hard to part with; the ladies from that generation always does. She had beautiful glassware from 1910, but not enough to make a complete set among any of them. A trunk full of old pictures and documents. My stepfather’s World War II memorabilia. A pair of stirrups belonging to his uncle. A stereoscope and cards. Remnants of his rock and gem collection, which I’d helped my mother move around for thirty years.

And there, tucked into the midst of it all, I came across Marie Baker’s diary. I didn’t hastily discard it or lose it. That’s a miracle.

My Aunt Elaine was there helping me, and when we’d take breaks for coffee, I’d read a little of the diary aloud. We’d talk about Marie’s remarks. Her voice became real to us—more than just lines on a page. Before long, we were invested in her story.

+++++

Fort Worth, Texas

+++++

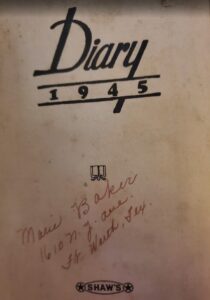

The inside front page.

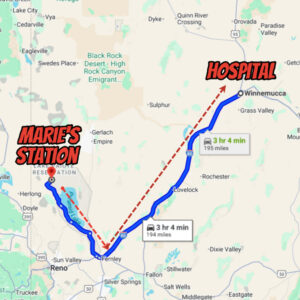

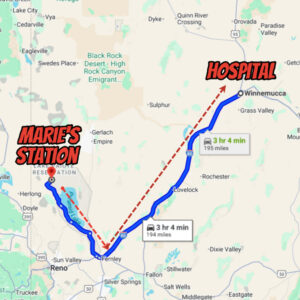

The diary’s story began on January 1, 1945.

“Dear Diary:

I guess this is as good a way to start the New Year 1945 as any—by working, I mean.

We have added a new member to our household, a gal by the name of Gladys Montgomery. What a pair we do make!

We act alike, talk alike, and look alike! (Or, so everyone says.) And we are two prize gigglers.

Rather silly, but we like us that way.

And this is a good ol’ ‘time and a half’ day at work. They don’t come along very often, as we all know!”

+++++

Marie Wasn’t a Poet, But We Were Hooked

+++++

That entry wasn’t especially descriptive, and that was about as good as Marie’s prose got. But still, her diary was like a movie in living color unfolding in our heads. We took a break from sorting through my mother’s life while I read those plain words from 1945, written by a country girl… and soon, we were in Fort Worth with Marie, lock, stock, and barrel.

Right away we learned there were four girls living in a rented house at 1610 New York Avenue. (And yes, the house is still there on Google Maps—albeit worse for wear, 80 years later.) They were having a grand time. They had places to walk to, buses to take them downtown and to the movies. They were making real money and had important factory jobs for the war effort. They were meeting loads of new people.

Early in 1945, Marie mentioned she was feeling old. She was 29. She would be 30 on her next birthday, for Heaven’s sake—an “old maid.” There wasn’t anything particularly dramatic in any single diary entry, but reading it aloud and talking about it made Marie larger than life.

Our anticipation had a low bar; sometimes we’d wonder: Would Marie sew a new dress? What was her mood that day? Did she learn something new at work? What movie were they going to on Saturday?

Jobs like Rosie the Riveter during WWII

+++++

A Job Like Rosie the Riveter Had

+++++

We’ve all seen the posters of Rosie the Riveter. That’s the kind of work Marie did, only she was involved in managing blueprints and schematics, finding and delivering them to other employees. She also became a floater who worked in several different positions on the line.

She and her roommates had left their families for factory jobs in the city—jobs usually done by men.

None of the roommates came from wealth. They left home to better themselves—even if it wasn’t by going to college.

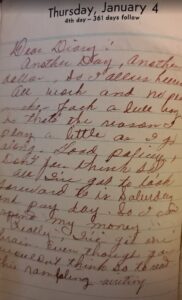

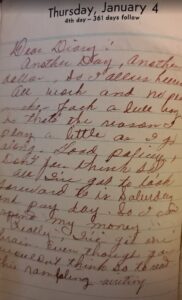

Marie’s diary entries were often just a line or two, though some covered a full page. One thing was constant—she never skipped a day. It felt like she had been journaling for years and couldn’t go without writing something.

Eventually, we learned Marie worked at an aircraft factory. A little Google research suggested it was probably Consolidated-Vultee Aircraft Corp., a Fort Worth company that employed 32,000 people during WWII.

Marie described her favorite roommate, Gladys Montgomery, as a hilarious blue-eyed blonde. Since Marie described them as looking alike, I figured she must have been the same. She didn’t mention either of them being notably tall, short, or petite—so I imagine they were average height and build.

Marie and Gladys sewed most of their clothes and did it often. When they teamed up, Gladys ran the seams through the machine while Marie pressed them open and flat at the ironing board—an ingenious way to speed up the process.

I searched online for photos of Marie, but none turned up. I did find her family on Ancestry. Marie was born to James L. and Miller Abigail Baker in Liberty, Texas on November 16, 1916. (Yes, “Miller” is listed as her mother’s first name.)

Marie was a caring daughter. She sent money home from every paycheck. On January 13, 1945, she traveled from Dallas to Houston, then by bus to Liberty for a visit—she had 14 days of paid vacation. Marie saw all her siblings, including her twin sisters, Vera and Era, plus their spouses and children. Of the six Baker children, Addie Marie Baker was the youngest.

The diary also mentioned her mother having a “spell” during the visit—it sounded like a stroke. There wasn’t much to be done, but her mother improved slightly before Marie returned to “Cowtown,” as she called Fort Worth.

The diary is filled with mundane moments, but isn’t that what builds a life? Marie and her friends were going to the park and movies, window shopping, chatting with people on buses and trains, or being flirted with at a diner. She also wrote about feeling sick from cramps and nausea during her cycle.

Sprinkled throughout were cryptic mentions of “a certain fellow” or “R.H.” She never named him directly, but in the section for addresses, she listed “PFC R.N. Howard.” Was that him? It’s impossible to say.

At one point, she wrote that R.H. brought over “their” new car—a yellow Ford—and took her for a ride. The way she phrased it made me wonder if she helped him buy it.

The whole situation felt “off.” He didn’t call or take her out regularly, but she was clearly smitten. He dropped by occasionally, sometimes took her out for a burger, or just hung out at the house. The diary describes that one night, R.H., Marie, the other girls, and their beaus laid out on blankets in the yard to stargaze, but the thread of subtext running through Marie’s days was clear: R.H.’s presence kept her from dating other men. Even though she got attention from attractive, higher-ranking soldiers, she wasn’t receptive. She received letters from other suitors and politely responded, but her heart wasn’t in it.

Aunt Elaine and I wanted her to dump that scoundrel.

+++++

Training to Become a Train Order Telegrapher

+++++

Fortunately, Marie was good with her money. She had savings.

By early 1945, the war was nearing its end. Soviet troops liberated Auschwitz in January, and Allied forces were freeing other camps in the spring. Factories would soon begin shutting down.

Marie was laid off in June, and she expected it. It didn’t seem to upset her. She collected her final paycheck, went home to visit over the July 4th holiday, and when she returned, she and Gladys—also laid off—enrolled in a telegraphy course.

Marie was offered a job as a train order telegrapher with Western Pacific Railroad. She would be stationed in Sand Pass, Nevada, a rural, mountainous, undeveloped part of the U.S., exactly the kind of place that needed telegraphers to communicate with trains.

Typical Depot Telegraph Station, 1870s. Source: “The Telegraph,” Harper’s Magazine, August 1873, 332.

+++++

Ending a Bad Romance

+++++

By then, Marie had had enough of R.N. Howard. She wrote in her diary that someone she cared about had lied to her.

A week before she was to leave for Nevada, R.N. Howard visited. He was shocked to hear she was leaving. He took her to dinner and begged her not to go. She said she had to. He promised to come back the next night. Of course, he didn’t.

That made it easier for her. She wrote, “At least this time, I wasn’t the fool.”

+++++

Western Railroad, Sand Pass, Nevada

+++++

Marie described traveling by bus and train to Sand Pass. She had packed herself up and gone a thousand miles from home to make something of her life. I can’t imagine going to such a desolate place.

She described her new home, her work, and her thoughts about friends returning (or not returning) from the war.

Her job paid $200 a month (around $3,600 today). It was hard work. She was the new kid and got the night shift. She didn’t complain.

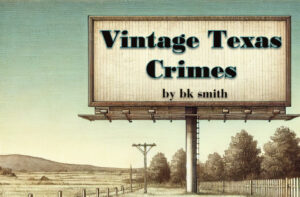

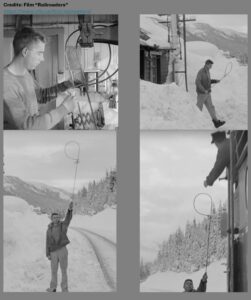

What a Train Order Collector Does | Credits: Movie, Railroaders | Click to expand.

She listened for incoming telegrams, copied them onto official order forms, clipped them to a hoop on a long stick, and stood by the tracks so the conductor could grab the orders in motion. Sometimes, they passed one back.

It was the only way to communicate in the Sand Mountains. This system saved time and money because trains didn’t have to stop.

Her “station” was a plank-floored wooden building. She lived in a nearby boxcar. No plumbing. She pumped her water and used an outhouse.

Only one coworker, Bill Wilson, her boss, was around when she worked. She got along with him just fine, but imagine that: Few people to talk to, pitch-black night, and you’re out on the track with that hoop, praying you don’t mess up.

+++++

September 1945

+++++

From the GSA website, a Samoa Girl Scout Cookie, my personal favorite.

Back in my real life, June 2020, on one of those afternoons, Aunt Elaine and I made coffee and found the cookies we’d been enjoying while we read—they tasted like Girl Scout Samoas.

By now it was September in Marie’s life. Only three months to go. We were already dreading the end. It felt like our favorite Netflix series was about to wrap up.

Something good had to happen. Maybe she’d fall for Bill, and we’d get a happy ending. I read:

“September 19, 1945

Dear Diary,

It sure looks like I am stuck on this third shift. Boy, I’ll tell you that it is getting me down!

Well, it looks like it is positive now about M.

Bill let me go to bed about 5:30 a.m. this morning. It sure helped me, too. Went to Flanagan as usual with Mr. Bonaham. Got a C.O.D. order from Sears. Dreamed about Sanders this morning and darned if he didn’t walk in this afternoon.

Gee! Life gets quite exciting at times.

Oh, but right now, I am a very sick woman. I wonder what I ate. Boy, I didn’t ‘urp’ but five times. I think Bill got sick, too.”

So Marie wasn’t feeling well. She thought she had food poisoning. “Positive about M.” meant a girl named Martha was going back to Texas. “C.O.D.” meant cash on delivery—she paid for a Sears package. And, to be clear, Sanders was a coworker, not a love interest.

I turned the page.

“September 20, 1945…”

Blank … nothing. I flipped through the last three months of pages all the way to the back.

“That’s it,” I said.

Aunt Elaine was shocked, too. She believed me, of course, but had to look for herself; What had happened? We’d spent over 250 days with Marie. She never missed an entry.

I grabbed my laptop and tethered it to my phone (Mother’s house didn’t have a connection to the web.) Finally, I opened up Ancestry dot com and typed in her name.A minute later, I told my aunt, “Marie died the next day.”

What a gut punch.

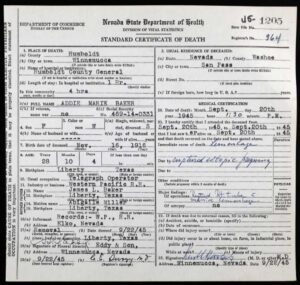

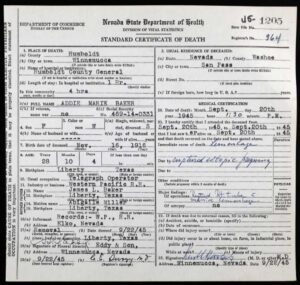

Marie’s Death Certificate that told us she had passed away. Click for larger image.

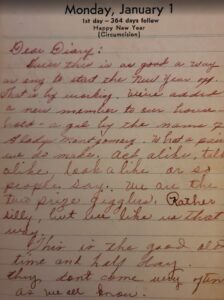

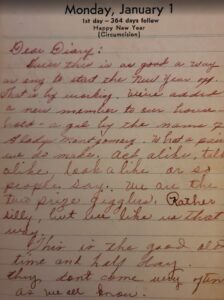

Marie passed away the afternoon of September 20 at Humboldt County General Hospital in Winnemucca, Nevada—200 miles from Sand Pass.

The death certificate said she lingered at the hospital for four hours. The trip to the hospital was three hours. She must have collapsed that morning. Maybe she never made it to work.

The timing said that around 7:00 a.m. that morning someone put her in a car or truck and rushed her to Winnemucca. (I tried to find historic train routes, but no luck. We will assume they drove.)

Her cramps in Fort Worth? We now know they were signs of endometriosis, which increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy. Her fallopian tube ruptured, and she bled internally … “massive hemorrhaging” the death certificate said.

It had been seven weeks since she’d last seen R.H. Aunt E and I agreed that would be the right timing.

I was furious. She died alone in Nevada. I wanted to blame R.H. I wanted to rip his teeth out. But he’d have been over 105 by then—long gone. Still, no one could ever repay what he owed her.

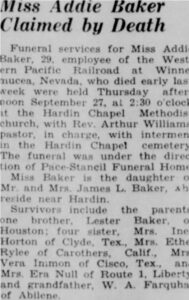

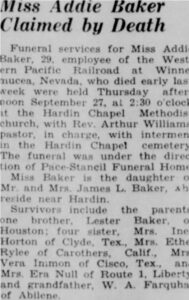

Click to see larger image of Marie’s Obituary.

I wonder if her family ever knew about him. Or did they only know their unmarried daughter died suddenly, leaving whispers behind in Liberty?

So, I said all that to say this…

Addie Marie Baker wasn’t just a girl who “got herself in a family way.” She was a good person. Her story deserved telling.

She came from the Greatest Generation. She was a loving daughter, a caring sibling, a loyal friend. She supported her parents, served her country, walked away from a bad romance, and faced life bravely.

She was so courageous and tenacious… and there’s no way PFC R.N. Howard—whoever he was—was braver than Marie.

Thanks for your story, Marie. Rest in peace.

Elaine and I have your back, girl.

+++++

Below are a few bonus images of pages from the diary and a few “treasures” found in my mother’s house.

I’ll be back soon—with a crime story next time.

(And I’ve got a feeling Marie Baker might have more story left to tell.)

Hugs, everyone. Thanks for following Vintage Texas Crimes & Stories.

—Brenda

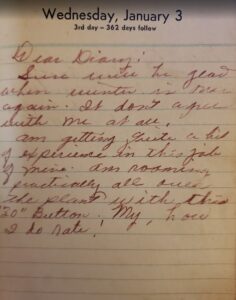

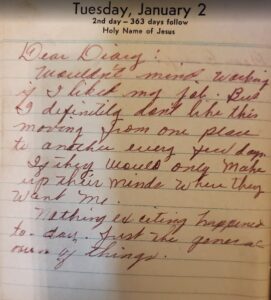

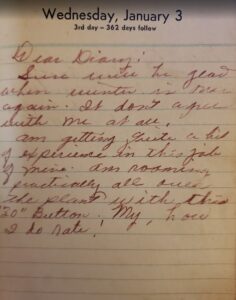

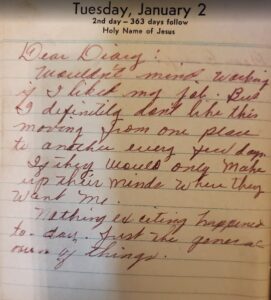

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Sand Pass in the Sand Mountains – Click to enlarge.

Treasures in Mother’s House

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge. We found these and a few more in a bucket of rocks. Straight to the safe deposit box!

A fraction of a fraction of the rocks my stepdad had. Click to enlarge.

Pictures from my mother’s trunk.

Pair of stirrups from the 1890s

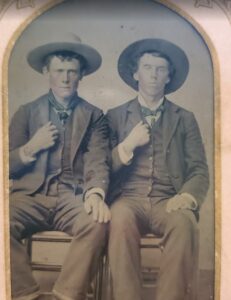

Two cowboys all dressed up. (My step dad’s uncle and a friend.)